Interpretable Deep Learning for Regulatory Genomics

Deep learning is being applied rapidly in many areas of genomics, demonstrating promising performance across a wide variety of regulatory prediction tasks [1]. Despite the promise of deep learning systems, it remains unclear whether improved predictions will translate into new biological discoveries because of their low interpretability, which has earned them a reputation as a black box. Understanding the reasons underlying a deep learning model’s prediction may reveal new biological insights not captured by previous methods. Our research develops methods to interpret deep learning models through design principles, interrogation methods, and robust training.

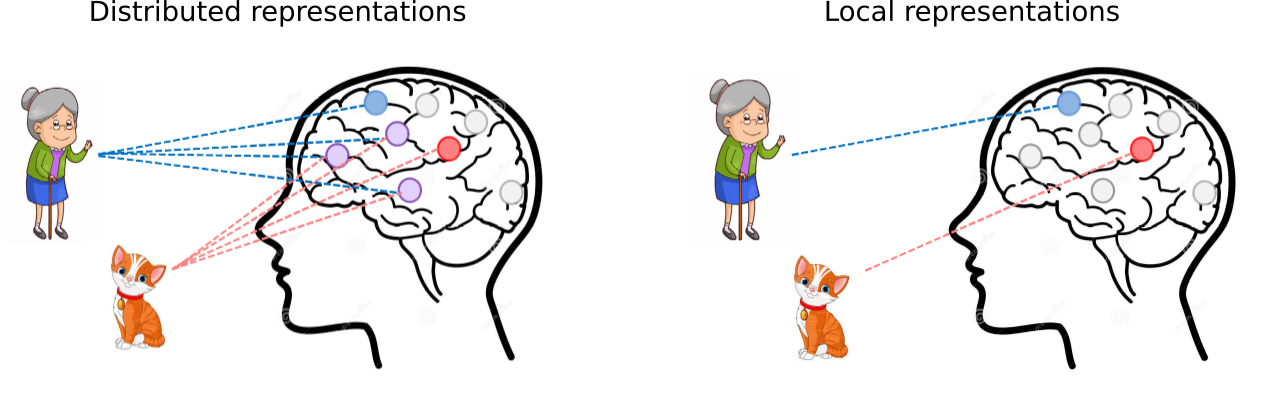

Design principles can guide parameters to learn human-interpretable, biologically-meaningful representations with an inductive bias (Fig. 1). Towards this, we have previously shown that the downsampling intermediate representations in deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs), a popular modeling choice for genomics, directly affect the extent that biological features, such as sequence motifs, are learned in each layer [2]. We have also demonstrated that highly divergent activation functions also encourage CNNs to learn more interpretable representations [3]. We are currently exploring how hybrid networks that build upon convolutional layers with attention mechanisms can be utilized to uncover complex motif interactions [4], the so-called cis-regulatory code.

Figure 1. Distributed representations recognize features, in this case a grandma and a cat, by integrating partial feature representations from many different neurons. On the other hand, local representations only employ a single neuron, a so-called grandma neuron, to recognize whole feature representations. In genomics, this corresponds to learning whole sequence motifs (local representations) or partial sequence motifs (distributed representations), which are difficult to interpret.

We are also interested in developing interrogation methods to access representations learned by deep (black box) models. We developed an interrogation method that uncovers global feature importance with synthetic sequences. This framework was instrumental to show that ResidualBind – our state-of-the-art deep learning model that is trained to predict sequence specificities of RNA-binding proteins – learns features not considered by previous methods [5]. We are expanding this methodology to uncover higher-order interactions of cis-regulatory elements, i.e. regulatory codes, from high-throughput sequencing datasets [6]. We have recently extended this method to computer vision, with the broader aim of understanding cancer prognosis from histology data.

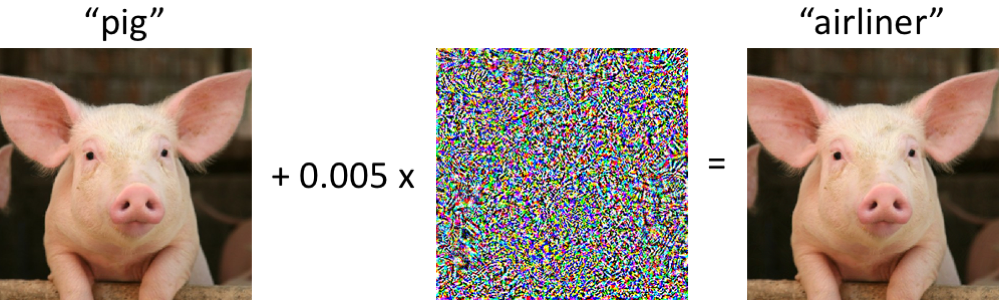

Robust training methods – adversarial training, Gaussian smoothing, and regularization – have been developed to improve the robustness of deep learning to adversarial examples, which are specially crafted perturbations added to data such that they are imperceptible to humans but can easily trick a state-of-the-art classifier (Fig. 2). There is growing evidence that adversarial training also leads to more robust features. We have observed deep learning models that learn robust features through design principles and robust training methods are generally more interpretable with attribution methods [7], [8], [9]. We are interested in establishing robust training standards for genomics and, more broadly, understanding the properties that make deep learning more robust and trustworthy.

Figure 2. On the left, an image of a pig is correctly classified by a state-of-the-art neural network. After a small perturbation is added to every pixel of the image, the new image (on the right) is visually very similar to the original image, but now the neural network predicts it is an airliner.

Language Models for Biological Sequences

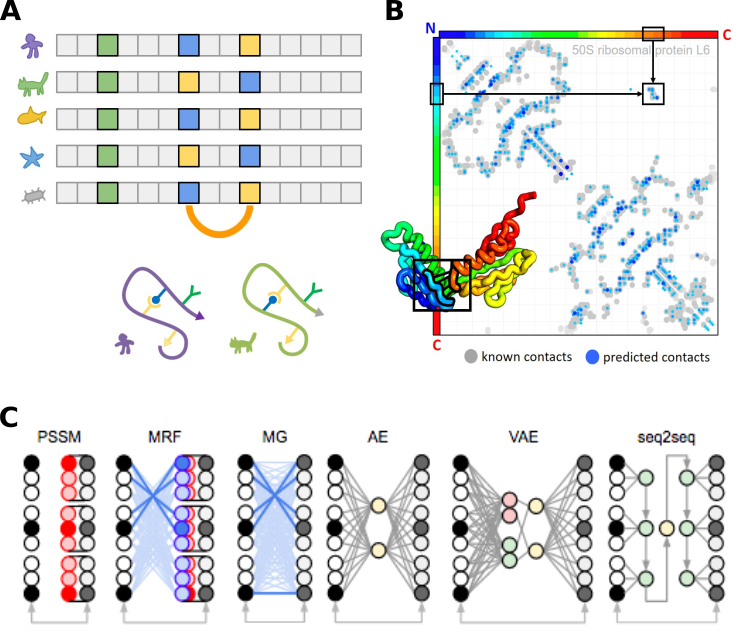

Multiple sequence alignments of proteins inform statistical models of evolutionary constraints linked to function (Fig. 3A), which include site-independent conservations and pairwise coevolutions. These models can then be repurposed to: score mutations in protein sequences, predict protein contacts (Fig. 3B), search for homologs, and design proteins. There has been growing interest in replacing traditional models – Position Specific Scoring Matrices (PSSMs), Markov Random Fields (MRFs), and Multivariate Gaussians (MGs) (see Fig. 3C) [8] – with alignment-free deep generative models [9] – variational autoencoders (VAEs) [10] - and language models based on transformers, but tailored with biological priors [11]. We are interested in interpreting these promising class of models to understand how they build representations and how to harness them to push the boundaries of basic science and cancer biology.

Figure 3. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of homologous protein sequences. Positions with the same amino acid are conserved (green column). Positions that are in structural contact can exhibit covariation (coupled columns covarying blue and yellow). (B) Example contact map shows protein positions from N to C terminus. Grey dots represent known contacts from x-ray crystallography, while blue dots represent covariation predictions by an MRF. (C) Graphical representation of statistical models for sequence analysis. (Images courtesy of Sergey Ovchinnikov)

Figure 3. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of homologous protein sequences. Positions with the same amino acid are conserved (green column). Positions that are in structural contact can exhibit covariation (coupled columns covarying blue and yellow). (B) Example contact map shows protein positions from N to C terminus. Grey dots represent known contacts from x-ray crystallography, while blue dots represent covariation predictions by an MRF. (C) Graphical representation of statistical models for sequence analysis. (Images courtesy of Sergey Ovchinnikov)